The use of Real World Evidence in Covid-19 is growing, and that’s a good thing. Properly implemented, RWE has the potential to deliver solid results faster than Randomized Controlled Trials, as I explained in a previous blog post.

So I couldn’t miss the largest observational study published to date on the effects of (hydroxy-)chloroquine, in 96 032 hospitalised Covid-19 patients, from an international registry comprising 671 hospitals in six continents:

Mehra, M. R., Desai, S. S., Ruschitzka, F., & Patel, A. N. (2020). ‘Hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine with or without a macrolide for treatment of COVID-19: a multinational registry analysis’. The Lancet.

Unfortunately, this paper is an example of Real World Evidence and Big Data implemented in the wrong way. Data is powerful, but not a magic bullet, and this kind of low-quality literature is my inspiration for launching the COVIND Consortium of Individual Patient Data.

In this Lancet piece, I identified 3 flaws:

- No reproducibility

- No data traceability

- No review transparency

No reproducibility

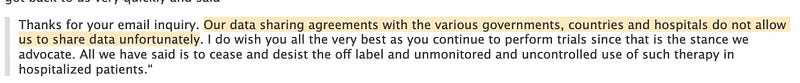

First, this study is not reproducible. Authors did not release their data, and it’s not even in their plans:

They argue legal pretexts, but it’s still a bad professional practice. Their data is a black box. In terms of reproducibility, this paper doesn’t meet community standards we have in machine learning, where most authors release their data and code on GitHub, and sometimes even build a ready-made container for one-click reproducibility on Google AI Hub, or other cloud platforms.

As expected, this data secrecy implies some weird stuff. For example, some critics, like in this blog from Columbia University, noted more deaths in this Lancet paper than reported by Australian authorities. Are Australian authorities hiding something, or did Lancet authors fabricated data for their cherished conclusion? I trust Australian authorities more.

A lot of other issues spill around in this crazy dataset, here and elsewhere. Garbage in, garbage out.

No data traceability

This Lancet paper also has no data traceability. Authors didn’t release the names of people who were responsible for data collection at hospitals. That’s the second black box. The paper only has 4 co-authors (ridiculously small for medical literature standards), and only one person was responsible for data acquisition: Sapan S Desai. How could he curate a huge dataset of 96 032 patients alone, so quickly? Is his company Surgisphere magical? Surgisphere only has 6 employees on LinkedIn. That’s insane.

Surgisphere claims to be “a leader in healthcare data analytics”, but their LinkedIn posts only have 1 like (a self-like!), and their oldest post is 2-months old. This bold and shady company seems a bit early-stage for leadership claims. It’s not the Google of health data.

- My tip to Sapan Desai: next time, pepper with fake LinkedIn profiles, and fake likes. It could be useful for growth hacking.

Why didn’t doctors and their labs try to stick their names on this prestigious Lancet paper? So many grants and tenures missed.

As a comparison, in particle physics, the important paper discovering the Higgs Boson particle at the Large Hadron Collider has 5,154 co-authors.

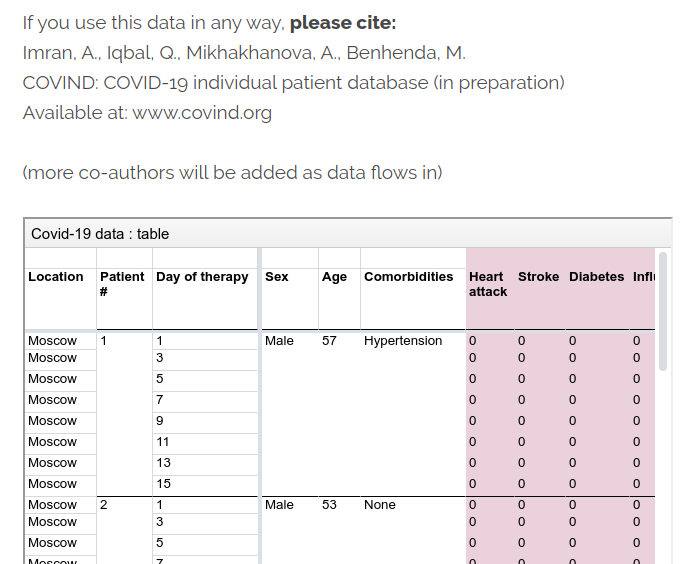

At COVIND data consortium, we are building a network of local doctors, who are also scientific partners. They put their names on all papers where their data is involved. They often tell me that’s their first condition for collaborating. That is not only to acknowledge their scholarly contribution. Their signature is also a public endorsement of the dataset they release, and a key link in the data traceability chain. That’s important when raw identified data is inaccessible for privacy reasons.

Of course, mistakes can happen, we are moving fast, but we implemented transparent error-correction procedures.

No review transparency

Lancet did not release the names of the referees (if any). Yet another black box. So the only signed editorial validation comes from Lancet editor-in-chief Richard Horton.

Richard Horton has an old political conflict with the US President. Donald Trump happens to be a big fan of Chloroquine, and Trump doesn’t care about Randomized Clinical Trials, and about science in general. Horton is certainly tempted to prove him wrong. In this bestial battle of egos, did Horton feel so insecure as to let a fraudulent submission slip through editorial filters? Oups!

Richard Horton published several political rants against Trump in The Lancet:

I don’t trust Fox News about global warming, so why should I trust The Lancet about Trump-approved Chloroquine? Fake news all around.

As written elsewhere in The Lancet (I love it as a political outlet, I am left-wing too!): “public health should not be guided by partisan politics”

That’s true both ways.

As a left-wing citizen, I agree with Richard Horton when he says that this pandemic is “the biggest science policy failure in a generation”, but I am surprised he wanted to be a part of it. So ironic.

From the ashes of the Lancet, I am still hopeful that a new era for data-driven medicine will emerge, based on three pillars: reproducibility, traceability and transparency.