The latest retractions by the Lancet and the New England Journal of Medicine are notable victories for open science. These hoaxes were more than obscure scientific literature. They had immediate consequences on medical practice and policies. These retractions are not the first scandals for the Lancet and NEJM, but they are among the most striking. They exposed in broad daylight what happens when science can’t breathe.

I prepared timelines to better understand the sequence of events, and learn from them. The fraud scheme didn’t start with the Lancet or NEJM publications: earlier, the same gang of fraudsters (Mehra, Patel and Desai) posted an influential preprint.

If I forgot something, feel free to ping me on Twitter (@mostafabenh), or better, edit the blog yourself and submit a pull request on GitHub (yes, this blog is open-source).

Consequences of the frauds

The Lancet fraud

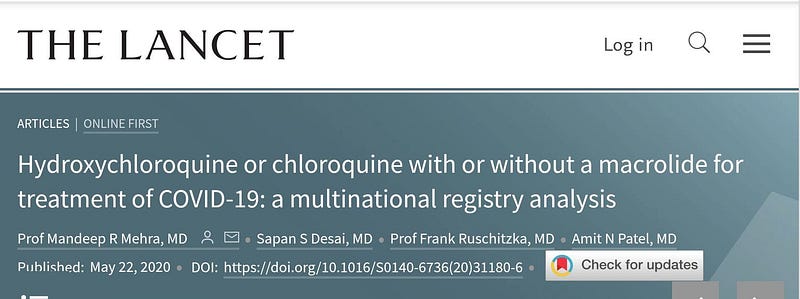

- 22 May

Publication of the Lancet hoax:

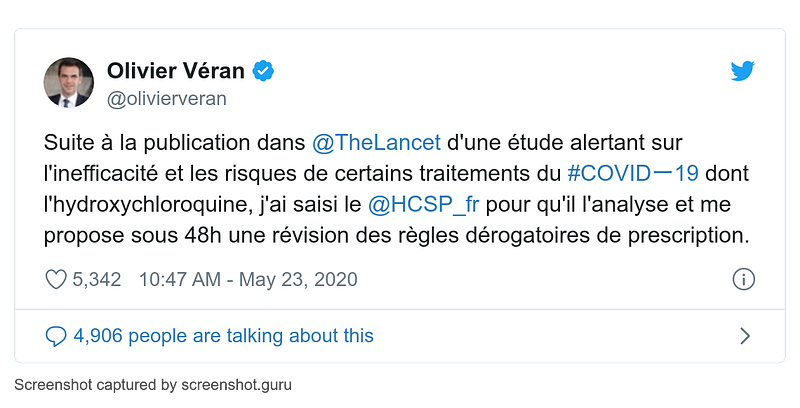

- 23 May

France minister of health Olivier Veran requests an emergency review of hydroxychloroquine prescription rules:

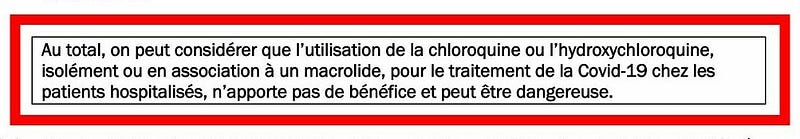

- 24 May

In less than 24 hours, the French High Council for Public Health (@HCSP_fr) warns against the “dangers” of hydroxychloroquine:

- 25 May

The World Health Organization suspends its hydroxychloroquine clinical trials:

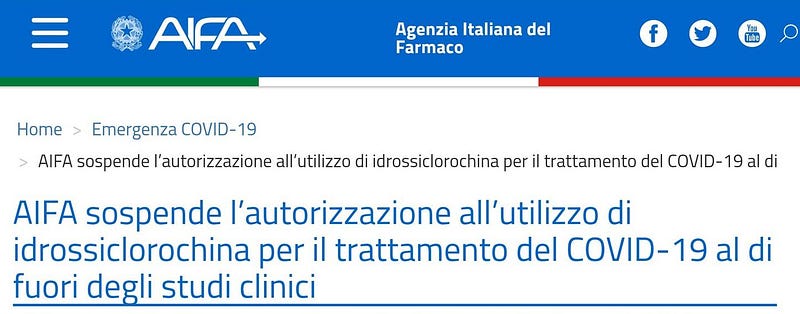

- 26 May

The Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) suspends authorization of hydroxychloroquine use for Covid-19 outside clinical trials.

- 29 May

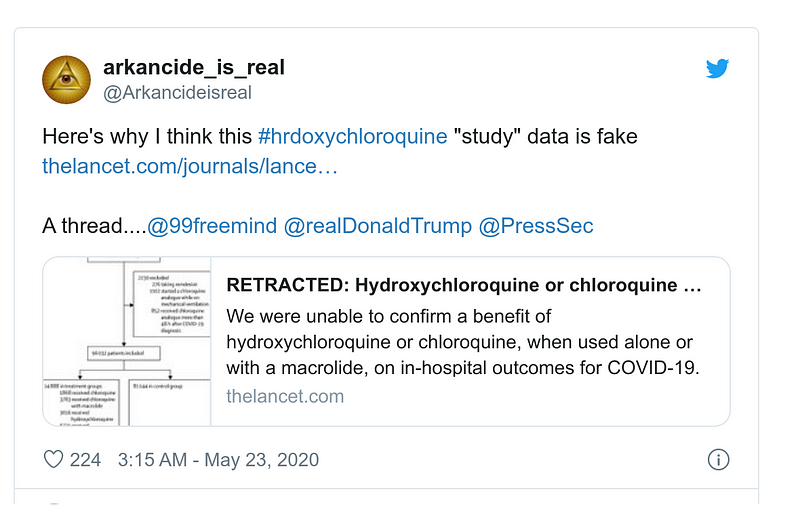

The United States terminates relationship with WHO. The Lancet fraud is not officially mentioned, but the coincidence is striking, because the Lancet fraud was massively denounced and retweeted by Trump MAGA fans, but still ignored by WHO (see in particular this tweet by @arkancideisreal on 23 May to the White House Press Secretary). For Trump, that was a unique window of opportunity for a controversial decision.

- 11 June

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology terminates relationship with Elsevier publisher (Lancet owner). The MIT doesn’t mention the latest Lancet fraud, but again, the timing is remarkable.

The preprint fraud

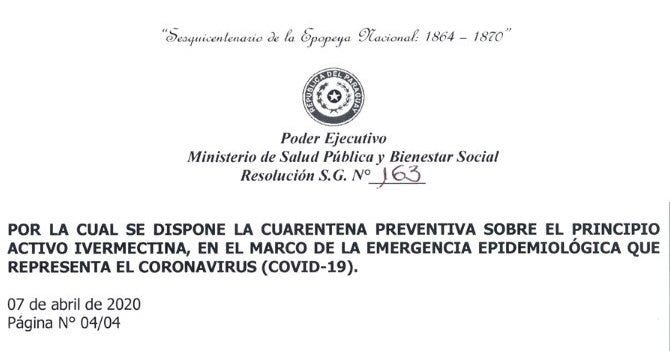

The first hoax was not peer-reviewed. Nevertheless, this preprint had significant impact on public health in Paraguay, Peru and Bolivia.

- 6 April

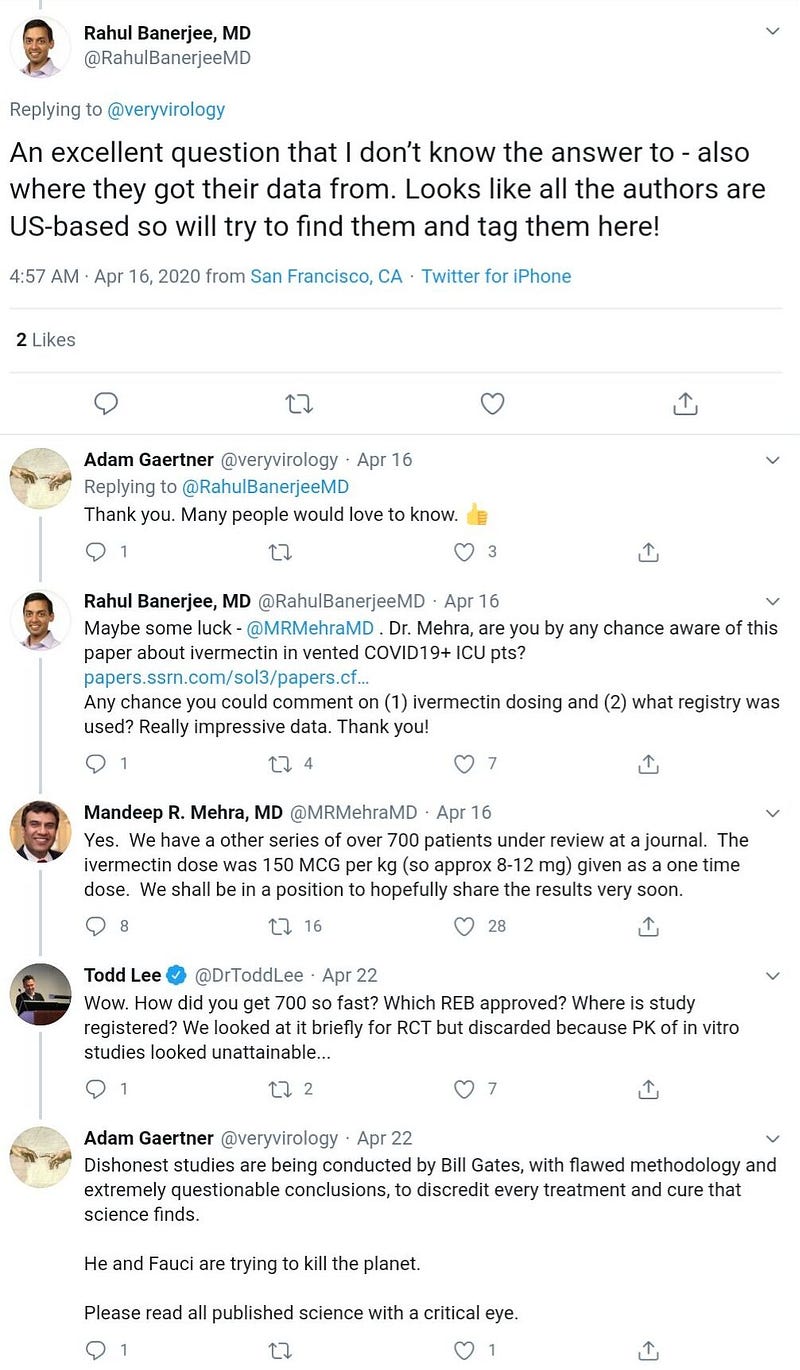

First posting of the preprint on SSRN server (incidentally, SSRN is owned by Elsevier, like the Lancet). It has been withdrawn from SSRN server since then, but the latest version (19 April) is still available here.

Grainger and Mehra are also co-authors of this hoax.

- 7 April

Paraguay minister of health, Julio Mazzoleni, restricts sale of ivermectin to prevent shortages.

- 2 May

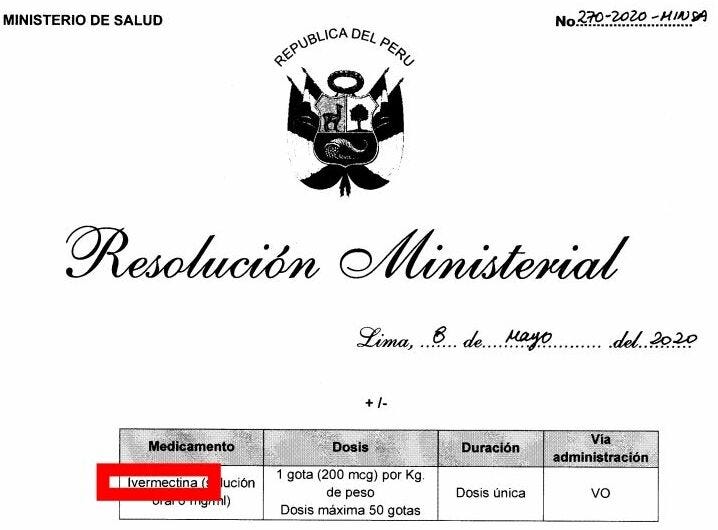

Gustavo Aguirre Chang, doctor from the San Pablo hospital complex in Lima, Peru, releases a white paper (non peer-reviewed) recommending ivermectin to be included in the national COVID-19 treatment guidelines of Peru.

- 8 May

Peru minister of health, Victor Zamora Mesia, requests the inclusion of ivermectin:

- 12 May

Bolivia minister of health Marcelo Navajas also includes ivermectin in the treatment of patients with coronavirus (COVID-19), under medical protocol and informed consent (without approval).

- 13 May

Large queues to buy ivermectin in Santa Cruz, Bolivia

- 16 May

In Trinidad-Beni, Bolivia, distribution campaign of 350,000 ivermectin doses to the population

The New England Journal of Medicine fraud

The impact of the NEJM fraud is harder to assess at the moment. Authors conclude a “confirmation” that blood pressure drugs angiotensin-converting–enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin-receptor blockers (ARBs) were not harmful in the Covid-19 clinical context. It still harmed patients by giving them a false sense of security:

Debunking the frauds

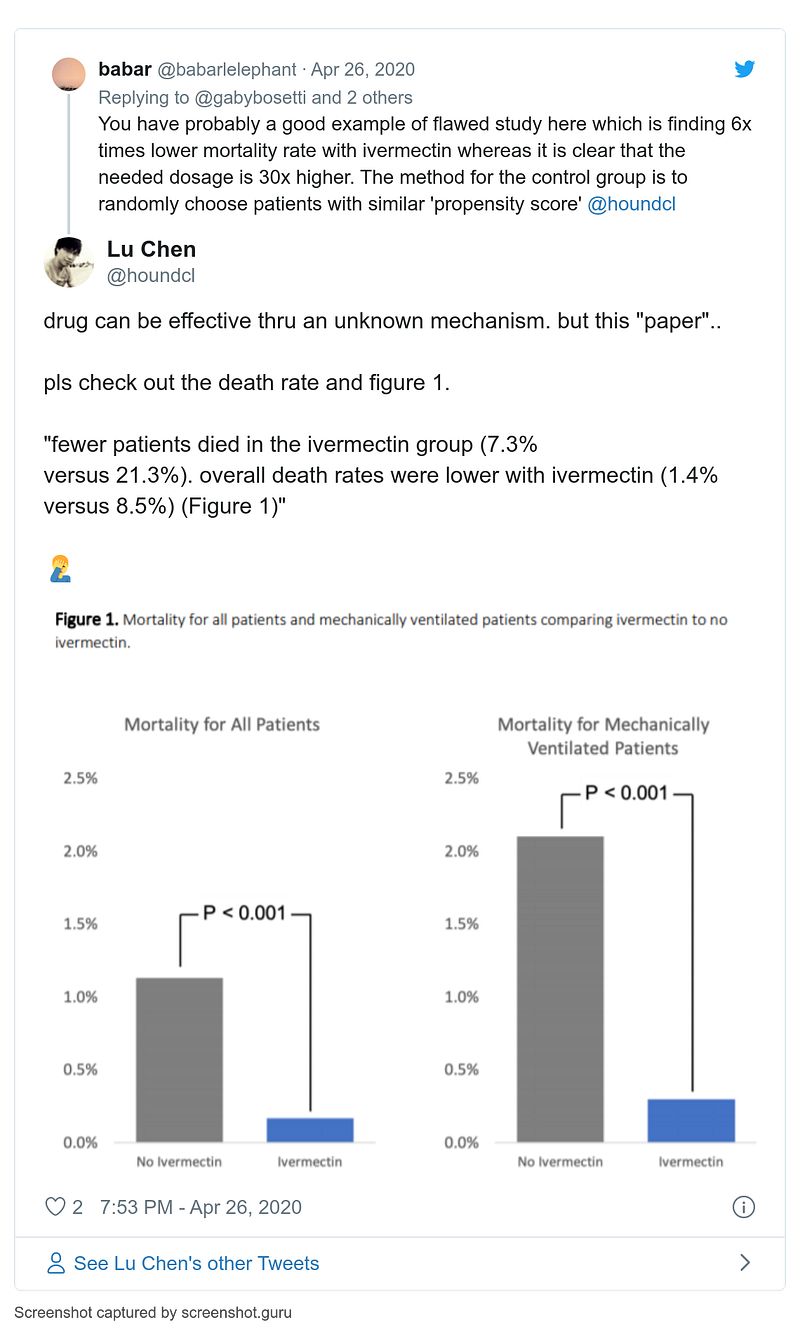

Preprint (non peer-reviewed)

- 6 April

Preprint posted on SSRN server.

- 16–22 April

- 19 April

- 26 April

- 13 May

NEJM publication

Despite 158 citations on Google Scholar, and a lot of tweets, I didn’t find anyone critical of this publication, until the Lancet scandal.

Lancet publication

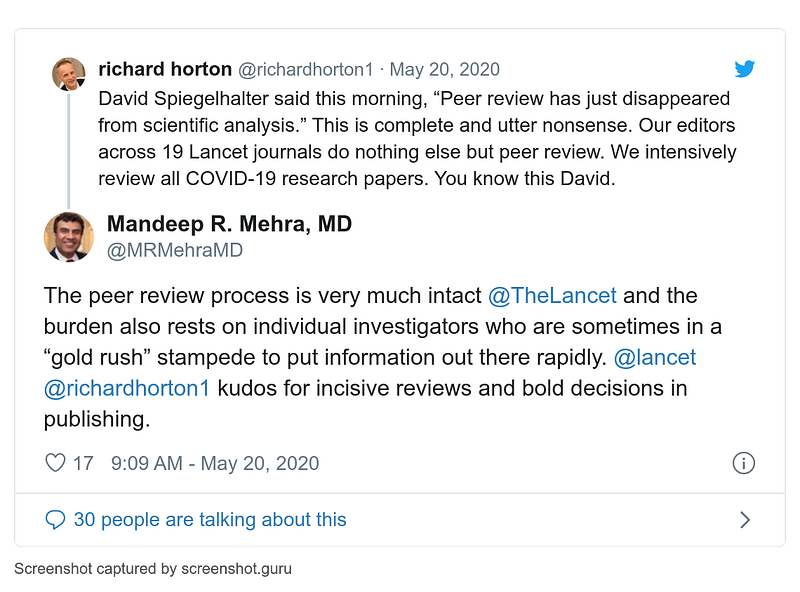

- 20 May

Before publication, fascinating tweets by Lancet editor Richard Horton and hoax author Mandeep Mehra:

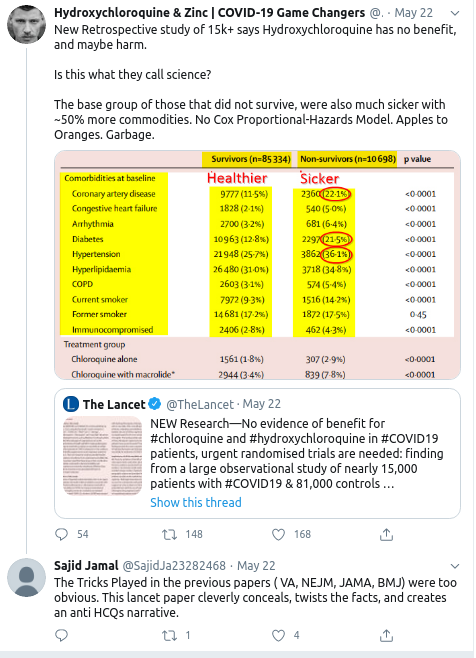

- 22 May

Article published

- 23 May

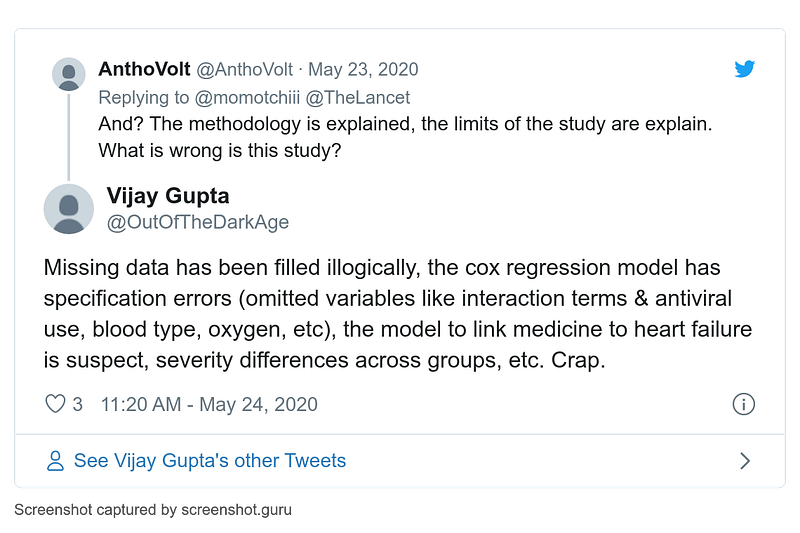

- 24 May

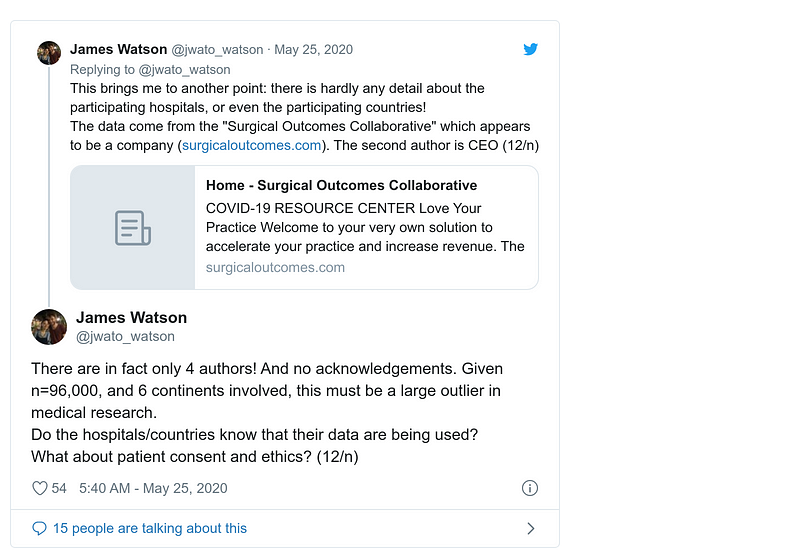

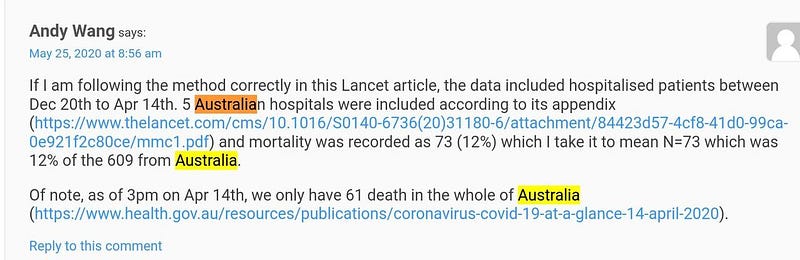

Blog post by Andrew Gelman about his email exchange with James Watson (full story on MORU website). See also comments inside:

- 25 May

Update by Andrew Gelman on his blog. Don’t miss comments inside!

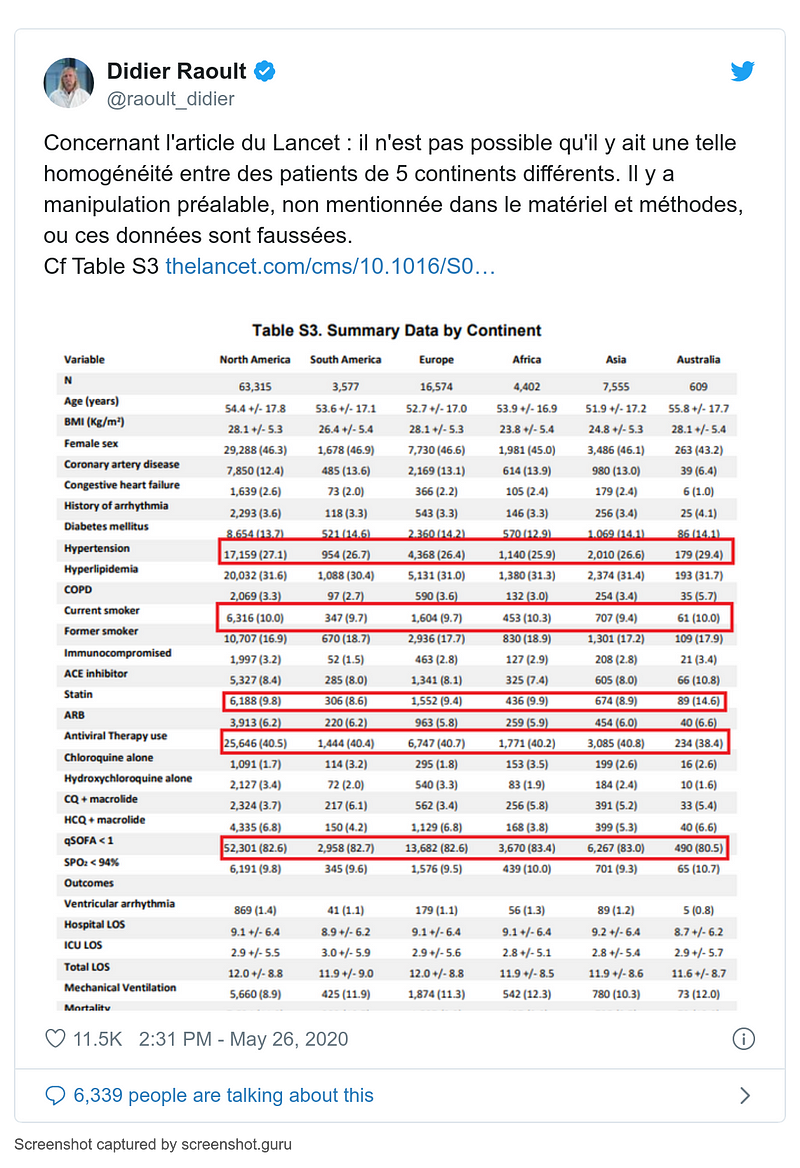

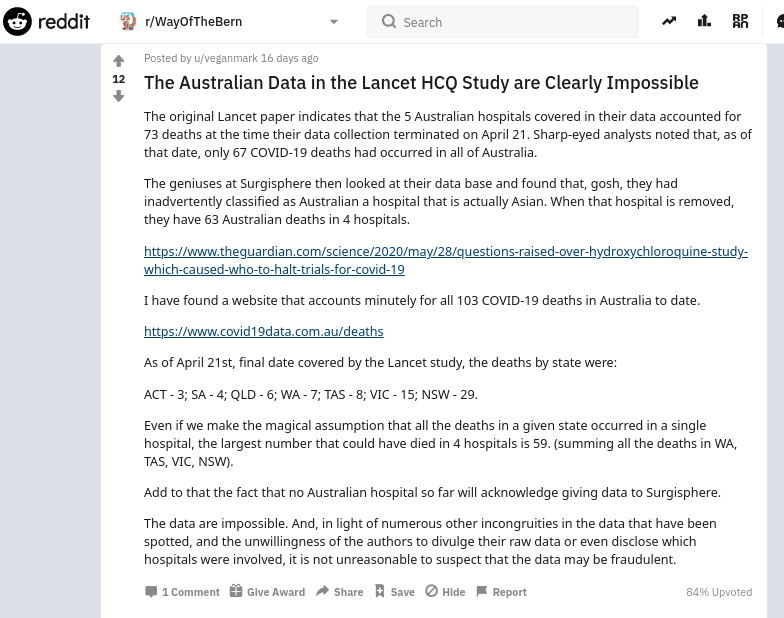

- 26 May

I decided to get involved when I saw Mehra refusing to release his data. It was the perfect opportunity for advertising my new open science platform COVIND, which relies on open data of Covind-19 patients around the world (learn more: https://covind.org) . Here’s my blog post (click on the image, read it!):

- 27 May

- 28 May

Open letter to Mehra et al and The Lancet by 182 signatories (including me!):

- 29 May

- 30 May

- 2 June

Open letter to Mehra et al and The New England Journal of Medicine by 174 signatories (including me!)

- 3 June

- 4 June

- 5 June

I didn’t include all critics, only those seemingly detecting the hoaxes. Again, if I missed anything, ping me on Twitter or edit yourself on GitHub.

What’s next for open science?

These 3 frauds got 3 different reactions:

- Lancet: fast and massive open review, Twitter trend, open letter, retraction

- SSRN preprint: sparse criticisms, no visible impact

- NEJM: nothing (until the Lancet paper)

Therefore, although the Lancet retraction was a visible success, it only happened after two successful frauds in SSRN and NEJM, which emboldened the Mehra gang of corrupted scientists. That’s far from optimal, open science can achieve much more. I think important questions are:

- Why did Peru and Bolivia health authorities apparently ignore the few tweets alerting about SSRN preprint flaws? (although their decisions about ivermectin seem balanced at the end)

- Why nobody open-reviewed the NEJM paper, before the Lancet scandal?

To avoid repeating these mistakes, improvements are needed on two fronts. First, health authorities need to grow their Twitter-awareness. In this area, there are lessons to learn from the US President Donald Trump. He leverages a sophisticated network of advisors on Twitter, who inform him in real-time, beyond the swamp of crooked science-bureaucrats.

On the second front, open review capabilities need to be reinforced. The NEJM hoax was flying under the radar for more than 3 weeks, and became a highly-cited publication (158 citations). How much of this dark matter is hiding in the scientific literature? There might be astronomical quantities of papers that nobody reads, everybody cites, but that are flawed.

One possible solution is to provide incentives for careful reviews. For example, introduce prizes for disinfecting the literature. In the Wild West of scientific research, bounty hunters can bring order.

In conclusion, these 3 scientific frauds demonstrate urgent needs for new initiatives in open science. I launched my own initiative, the COVIND platform of patient data, join at: https://covind.org